Despite the disruption caused by March’s terrorist attacks on Brussels Airport and metro, the NU-AGE final conference went ahead on Tuesday 5 April 2016. My flights were cancelled at the last minute, but I was able to travel up by train and attend.

What is NU-AGE?

NU-AGE is a large-scale one year EU dietary intervention project, run from five European centres, investigating if a Mediterranean diet adapted to the needs of the elderly could prevent age-related diseases (atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes, neurodegeneration and cognitive decline) and the chronic low-level inflammation that accompanies them (inflammageing). It hopes to cast light on the poorly understood relationship between food and health in the elderly, produce a new “food pyramid” and food guidelines for over-65s, and connect with a wide range of academic, national and commercial partners to make full use of the results. The study group were tested (blood, urine) before and after the project, with a small subset also tested in greater depth. They were also given frequent dietary advice, and provided with some recommended foods, including ones newly developed for the project. There was also a control group of equal size, who were enrolled in the trial and given a booklet.

The NU-AGE Final Conference

Opening of the NU-AGE Final Conference.

Not all the presenters or attendees were able to make it, and the conference was moved to a smaller room, but that did not dampen the enthusiasm of the study co-ordinator, Claudio Franceschi. He opened the day with an overview of the project and emphasised that not all results would be announced that day as the project would have exclusive access to the data for another five years. He touched on the decline in variety in the microbiome with age and the role of cytomegalovirus in ageing before pointing out that the greatest differences in the study were seen between countries and genders.

NU-AGE Project Coordinator Claudio Franceschi opening the NU-AGE Final Conference

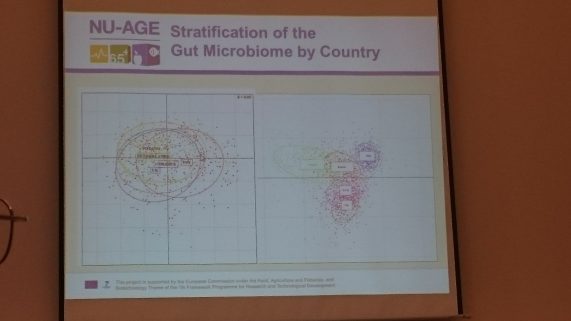

There was open discussion of the need to reanalyse data or take account of possible confounding factors, such as a placebo effect in the control group which may have caused them to adopt better habits and so enjoy improved health, which would mask the full effect of the health improvements seen by those adhering to the diet in the study group. There was also likely to be an effect from the magnitude of the difference between the NU-AGE diet and the standard diet in the study centre, e.g. the standard Italian diet would be closer to a modified Mediterranean diet than the standard Polish diet. Non-compliance with the diet by some of the study group also needed to be taken into account. Surprising or counter-intuitive results were displayed and discussed, with some preliminary results to be reanalysed in the light of later information. The striking diversity between the five centres (in existing diet, human genetics and microbiome) were also expected to have a strong effect.

Differences in diet and microbiome in the five study centres.

There were indications that the dietary changes reduced bone loss (independent of weight loss) and that although personalised diets might not be feasible stratified diets might be. Diversity in the microbiome was enriched even for study subjects who had a good mix of bacteria before the study, but the microbiome itself did not appear to have much of an impact in the overall intervention. The quality of diet eaten by the over-65s was found to be poor overall, with resources and proportion of income spend on food found to have a paradoxically negative effect on diet quality.

Attitudes to and perceptions of nutrition and health statements on food packaging varied greatly, with widespread scepticism in the UK despite a relatively high level of knowledge. The day finished with a presentation by several small and medium sized food companies who talked about the challenges of developing, formulating and packaging new foods that delivered more beneficial ingredients to the target audience. Some were available for tasting on the day, such as a Greek yoghurt with the dairy fats replaced by olive oil… but under EU regulations they were not allowed to call it a “yoghurt” precisely because of the lack of animal fat. The rule was designed to prevent adulteration of foods with cheaper oils, but this illustrates how creating new foods also runs the risk of stepping outside of traditional parameters used to define and regulate food.

Conclusions

It was fantastic to see so many aspects of a project gathered in one place, from the study design and recruitment, through retention and compliance, through to the detailed analysis (microbiome, genetics, bone health, cognition, inflammation, transciptomics, metabolomics), and social and technical support – plus the involvement of the companies who develop and produce food. The study has generated a wealth of data which will go a long way towards answering its initial questions, but there was some criticism of how the EU funding was structured – it covered the preparation for and actual running of the trial, but then stopped before the main analysis of that data was done, leaving researchers to do this in their own time. I felt this was particularly damaging as it risked the data being left unanalysed and not used to its full potential, which wastes the enormous amount of time, money and effort invested in the project.

For more updates on the study, follow the European Food Information Council (EUFIC) on Twitter (@EUFIC) or check the NU-AGE site (http://www.nu-age.eu/home).